It is altogether possible that Daniel Peacock watched the inauguration of the 44th President of the United States on a 1955 RCA TX 500 model television. A vintage tube that looks as though it broadcast’s live from a fish tank. Or maybe he decided to ditch the murky black and white transmissions of the RCA to watch a live feed from his computer that normally streams old time radio broadcasts that flood his studio. However, the former seems a more romantic and fitting gesture for this writer. The technological anomaly of watching a new President take the oath of office on a television that was first popular when Dwight D. Eisenhower wasn’t even considered a political relic, reflects Peacock’s own sensitivity of the past and his desire to make time honored images feel new again.

As part of an ensemble of 20 fellow Lowbrow artists, Peacock’s participated in Obama’s Campaign for Change and created works especially for the campaign. A pencil drawing on an 8.5×11 piece of paper depicts an Obama Lincoln hybrid, a mish-mash technique implemented in many of Peacock’s paintings. Lincoln’s tall and skinny top hat cannot conceal Obama’s trademark floppy ears. Abe/Barack’s slender bearded face and parted lips can barely hold a cigarette that bubbles rather than fumes tobacco. When reminiscing about the drawing a smile makes a part in Peacock’s lips as he explains that, “it was Lincoln with the big ears and the cigarette, almost Napoleonic, just sitting there. Very regal, very Lincoln-esque.” Handwritten above the figure reads, “Vote” with the “o” replaced by a heart. While this interview took place, President-Elect Barack Obama rode on the back of a train from Illinois to Washington D.C. just as Abraham Lincoln had done nearly 150 years ago.

His humble abode is a tranquil and isolated guesthouse hidden from the street in a South Pasadena neighborhood that also doubles as his studio. Several paintings from his upcoming show line the windowsill while the rest are discretely filed upright in between a small couch and a cabinet filled with personal treasures. A wall shelf boasting a partially solved Rubik’s cube, the casing of a transistor radio, “Thing 1” from Dr. Seuss’ Cat in the Hat, a 1920’s Mickey Mouse reissue stuffed animal that sits upright in the corner, a John Lennon “Yellow Submarine” action figure, and a picture with guitar legend Les Paul. The cabinet “supports” Peacock when he paints, as he works with his back against the objects and the incoming light. He looks at the cabinet and reflects that the objects are, “a mish-mash of important things and cherished things.” Peacock pauses and seems to take a mental inventory of each object situated in its exact place. The cabinet houses “photos and knick-knacks,” he explains. But the shelf is really much more than that, “it’s Daniel Peacock’s ‘trifecta of influence.’” The influence of 1930’s Mickey Mouse cartoons are immediately recognized in his canvases as the early Disney cartoons were confined to a linear aesthetic, one that Peacock has embraced. “Oh wow, that’s interesting,” he remarks surprised by the connection between a child hood favorite and his current works.

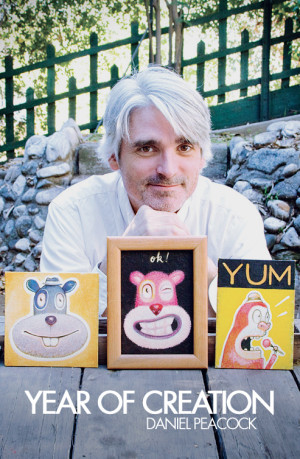

Peacock’s upcoming show Creation opens on February 6 at La Luz de Jesus Gallery, the brainchild of art collector Billy Shire. Peacock’s first solo show with Shire Everything but the Kitchen Synck was in 2005. Unsure of precisely how many works the show would include Peacock laughs, “I always overshoot or undershoot. Usually, it’s at least a baker’s dozen plus a half-bunch more in there.”

Peacock himself is a character, as illuminating and unpredictable, as the creations in his paintings. When describing his works he creates a dialogue for the narrative, imagining voices for his character’s that range in all registers. The voices illuminate an already quirky and whimsical cast of characters. Peacock’s arsenal of subjects are critters from an alternate dimension, friendly, hybrids, animals of different species co-existing fuzzy-wuzzy forget-me-nots, that are neither here nor there, rather go-betweens of a natural and utterly fantastical world. Peacock’s body of work vividly captures the imaginative spirit of a young boy who embraces the religion of Dr. Seuss. “I’m always going for trickery” he responds with a smile, “or a multi-dimensional thing. It might be a private joke that just never translates, you know? I’ve always thought that the impression of the work is rarely aligned with the intention of it—even people who create things can’t always define the intention.” The playful amalgamation of characters and are harnessed by the viewer’s arsenal of pop culture references like the innocence of early Mickey Mouse cartoons and the zany nature of Dr. Seuss. Regardless of our ability to understand exactly what the characters are meant to reference, they are figments of the artist’s belief. Peacock insists on the power of belief declaring that “When you believe in it, it’s alive somewhere. And if it’s alive in your mind it’s alive.”

Enlivening the past and re-imagining it in the present is a notion reflected in Peacock’s desire to paint on yellowed pages of nickel and dime books purchased from the library and old newspapers. One of his favorite papers from 1935 is framed and doubles as a table for a vintage typewriter and the RCA set. We read the text together, upside down because the glass is too heavy to move. “Look at that. This is from 1935!” he exclaims with a high- pitched inflection, similar to the tone he uses to animate the characters from his canvases. As his eyes scan the paper, the barrier of time and space disappear for Peacock and he begins to see similarities between 1935 and 2009. “There’s such an essence of stuff we hear about being so urgent and special but this stuff goes on forever, you know what I mean?” In Daniel Peacock’s studio, the past is never really past; it’s just on hold and waits patiently to be re-activated.

2009 is the year of something new. Dubbed the year of “Creation” the ritual of naming each year is a way for Peacock to chronicle his own artistic evolution. Sitting outside on his patio as the afternoon sun slowly slips away, Peacock looks around with a sense of contentment. “I made this happen because I believed it, and it happened. And I thought this is the beginning of belief.”